The Origin of “门当户对”

The term first appeared in the Yuan Dynasty drama The Romance of the Western Chamber by Wang Shifu. In one famous line, it states: "Although we are not equal, it is better than being trapped among thieves." Over time, this idea evolved to symbolize matching social statuses, particularly in the context of marriage.

Interestingly, some believe that “门当” and “户对” originally referred to decorative architectural features on traditional Chinese doors. While not official architectural terms, they became associated with the symbolic objects used to adorn gates and represent social rank.

The Role of "门当" in Architecture

“门当” refers to door knockers, which were integral to the design of traditional Chinese gates. These structures served both functional and decorative purposes. Placed at the base of door frames, door knockers were shaped either like drums or square blocks, often adorned with intricate reliefs depicting auspicious motifs such as:

Symbolism of Shapes

|

|

|

|

Over time, drum stones came to symbolize status and achievement. Initially reserved for officials, their use expanded during the Qing Dynasty as the sale of official titles allowed wealthy merchants to incorporate them into their homes.

Understanding "户对"

“户对” refers to door hairpins—wooden or brick carvings placed on door lintels or sides of gates. Beyond their structural role in reinforcing beams, these carvings were highly decorative, featuring auspicious patterns like “Wealth and Peace” or “Good Fortune.”

|

|

Architectural Classes of Gates: Dividing Social Status

Gates in traditional Chinese architecture were more than functional—they were symbols of social hierarchy. Doors were broadly categorized into two styles: building-type (independent structures) and wall-type (embedded in walls). Each type reflected the owner’s social rank.

Palace Gates: Reserved for Royals

The highest-ranking gates, such as those in the Prince Gong Mansion, were magnificent structures featuring five-room designs, door nails, and decorative stone lions. A screen wall often faced the gate, adding to its grandeur.

Common Gate Types by Rank

1. Guangliang Gate

2. Jinzhu Gate

3. Manzi Gate

4. Ruyi Gate

The Deeper Connection to "Well-Matched Status"

While “门当户对” is now a metaphor for marital compatibility, its architectural roots emphasize the importance of balance and harmony in design and status. The pairing of decorative elements, such as symmetrical door knockers and hairpins, symbolized equality in status—an idea that carried over into societal expectations.

Today, the physical gates are a testament to history, artistry, and the enduring importance of tradition. Whether in architecture or relationships, being "well-matched" remains a valued principle in culture

Source: VNbuilding.vn

The News 14/12/2025

Architectural Digest gợi ý Cloud Dancer phù hợp với plush fabrics và những hình khối “mềm”, tránh cảm giác cứng/rigid; họ liên hệ nó với cảm giác “weightless fullness” (nhẹ nhưng đầy) [3]. Đây là cơ hội cho các dòng vải bọc, rèm, thảm, bedding: màu trắng ngà làm nổi sợi dệt và tạo cảm giác chạm “ấm”.Pantone has announced the PANTONE 11-4201 Cloud Dancer as the Color of the Year 2026: a "buoyant" and balanced white, described as a whisper of peace in the midst of a noisy world. This is also the first time Pantone has chosen a white color since the "Color of the Year" program began in 1999. Pantone calls Cloud Dancer a "lofty/billowy" white tone that has a relaxing feel, giving the mind more space to create and innovate [1].

The News 04/12/2025

The Netherlands is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, with about a third of its area lying below sea level and the rest regularly at risk of flooding. As sea levels are forecast to continue to rise and extreme rains increase, the government is not only strengthening dikes and tidal culverts, but also testing new adaptation models. Floating housing in Amsterdam – typically the Waterbuurt and Schoonschip districts – is seen as "urban laboratories" for a new way of living: not only fighting floods, but actively living with water. In parallel with climate pressures, Amsterdam faces a shortage of housing and scarce land funds. The expansion of the city to the water helps solve two problems at the same time: increasing the supply of housing without encroaching on more land, and at the same time testing an urban model that is able to adapt to flooding and sea level rise.

The News 20/11/2025

Kampung Admiralty - the project that won the "Building of the Year 2018" award at the World Architecture Festival - is a clear demonstration of smart tropical green architecture. With a three-storey "club sandwich" design, a natural ventilation system that saves 13% of cooling energy, and a 125% greening rate, this project opens up many valuable lessons for Vietnamese urban projects in the context of climate change.

The News 10/11/2025

In the midst of the hustle and bustle of urban life, many Vietnamese families are looking for a different living space – where they can enjoy modernity without being far from nature. Tropical Modern villa architecture is the perfect answer to this need. Not only an aesthetic trend, this is also a smart design philosophy, harmoniously combining technology, local materials and Vietnam's typical tropical climate.

The News 25/10/2025

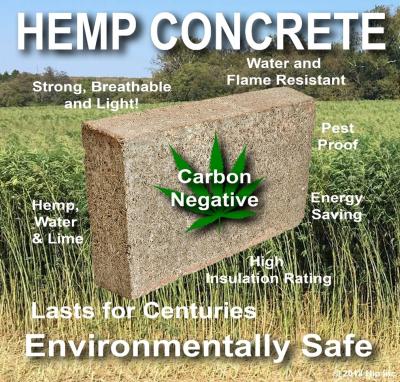

Hemp-lime (hempcrete) is a non-load-bearing covering material consisting of a hemp wood core (hemp shiv/hurd) combined with a lime-based adhesive, outstanding for its insulation – moisture conditioning – indoor environmental durability; in particular, IRC 2024 – Appendix BL has established a normative line applicable to low-rise housing, strengthening the technical-legal feasibility of this biomaterial.

The News 11/10/2025

Amid rapid urbanization and global climate change, architecture is not only construction but also the art of harmonizing people, the environment, and technology. The Bahrain World Trade Center (BWTC)—the iconic twin towers in Manama, Bahrain—is a vivid testament to this fusion. Completed in 2008, BWTC is not only the tallest building in Bahrain (240 meters) but also the first building in the world to integrate wind turbines into its primary structure, supplying renewable energy to itself [1]. This article explores the BWTC’s structural system and design principles, examining how it overcomes the challenges of a desert environment to become a convincing sustainable model for future cities. Through an academic lens, we will see that BWTC is not merely a building but a declaration of architectural creativity.